of endless Milky Way

for a star in the sea of stars,

and rest in starry bay.

translated by Viktor Horváth

June 8, 2021 – August 8, 2021

Curator

Judit Gellér

Robert Capa Contemporary Photography Center

Free admission:

Tuesday – Friday 14h - 19h

Saturday – Sunday 11h - 19h

Closed on Monday and holidays.

The exhibition

Introduction

The exhibition Starry Bay by Ábel Szalontai is a representative selection of a photo series that has been evolving for decades. The images and short moving pictures installed in light boxes lay out the world of seas and ports, and the stories of those living there and passing through. Szalontai is gifted in capturing the fascinating and perceptible encounters of water and shore, may it take place in photogenic Iceland, crowded Shanghai, Greece’s popular Corfu, Romania’s peaceful Sulina, or possibly in large industrial or port cities, like Gdańsk in Poland or Dublin in Ireland.

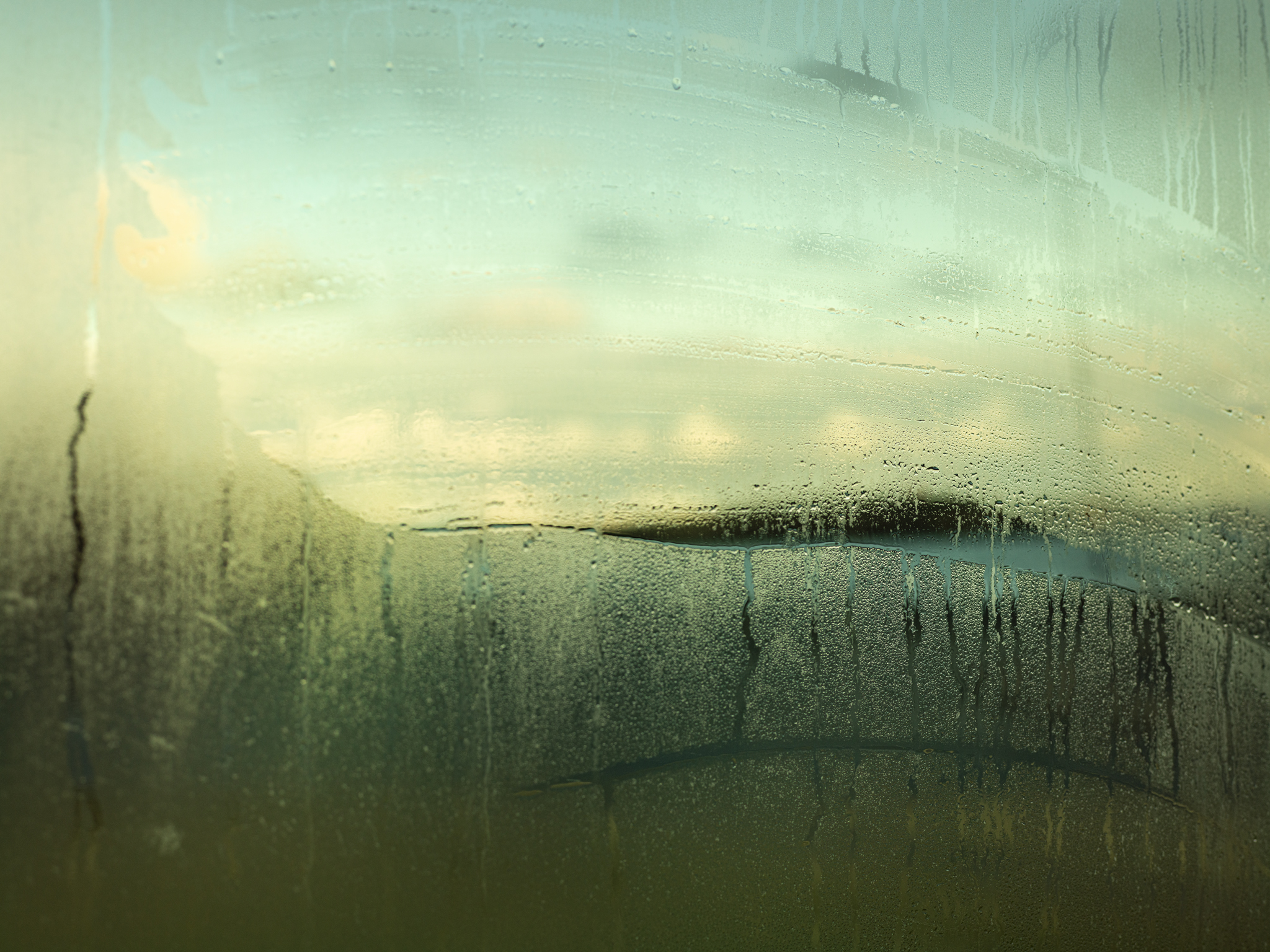

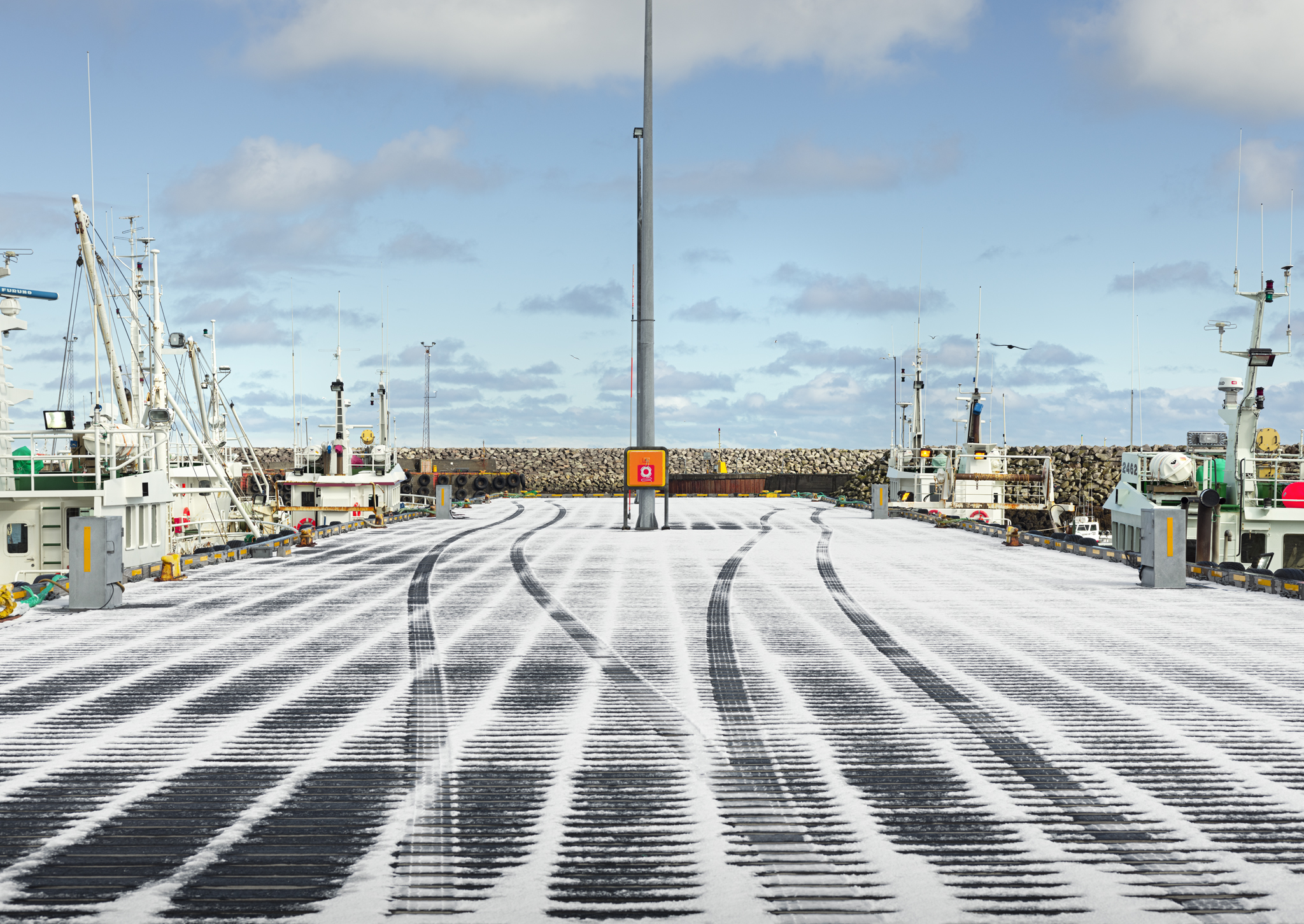

Starry Bay is the collection compiled by Ábel Szalontai. Waves easing off, ripples, splashes, and stormy waters. Gazes sweeping over the skyline. Buoys, fishing nets, hulls. Waiting for the suitable weather conditions for the ships to leave port. Sailors, fishermen, islanders, passersby. The harbor is the venue for encounters and goodbyes, arrivals and departures. Misty, sunny, night and snow-covered shores. Continuous buzzing, regardless of the time of day.

At the same time, the harbor is also a recreational, strategic, administrative, and economic hub, a scene for battles, exchanges and commerce. The cargo of the ships arriving from long journeys and faraway lands are piled up in unremarkable containers and barrels hiding exotic products and produce. The artistic depiction of ships looks back to thousands of years of tradition, starting from the hieroglyphs of Egyptian papyrus scrolls to the galleys appearing on Greek vases, the almost entirely authentic and accurate paintings of the Renaissance masters portraying the vessels of our age, and finally the photographic representations. With the passing of time, the galleys decorated with paintings and carvings gave way to the multiple-masted caravels serving in the Age of Discovery and colonization, and nowadays the ports are filled with heavy steel hulls, gigantic cruisers and liners. The act of navigation starts and ends with arriving at the shores.

“Near the sea, exploring the skyline, immersed in the crowded or desolated world of ports, I always find that somehow everything is about the past there. The present is the endless cycle of the repeated past. The importance of memories is heightened, the past is more important than the future. In addition, islands provide an extra sense of acceptance and inclusion, possibly because those living there still remember that they have arrived from somewhere else too. Harbors are seaside havens, resting places for the mind, which ages more slowly there than the body,” says the photographer about his images.

The photographs of Ábel Szalontai can only present one slice of the endless, visual repository of water. The quiet of his photographs generates tension: the abundance of symbols, the endless skyline, the little details of harbor life delineate these invisible stories.

Judit Gellér, curator

The past, the present and the future of the north

No one has lived here in a long time. The rusted roof blends in with the mountainside, which is also reddish in color. I’ve asked many people about who may have lived here, but no one seems to know anyone who did. It’s as though it were built and then abandoned with no one having ever made a home here. I notice a large crack across the living room window, and the glass in the front door is broken. The wind streams through it in bad weather. [...] I stand there on the stairs, feeling like I live in this house now, as though I had just stepped outside for some fresh air and was coming back in to talk to my family by the warmth of the fireplace.1

Sigrún Alba Sigurðardóttir

The light is tremendously important in the North during the darkest months of Winter. In January, when all the Christmas lights have been but away, it’s even more important than before. At 8 o’clock in the morning you can spot young children with rucksacks sneaking slowly along the pavements, listening to the characteristic crunching sound from their own winter boots tramping delicately on the dry snow

Looking at Abel Szalontai’s photographs from Iceland in the darkest of months, I sense how they have evoked hidden childhood memories in my body, at the same time as they document my reality today and make me reflect upon the existentially circumstances of daily life in this small community in the North I call my home. I experience the location of my life through the eyes of the outsider.

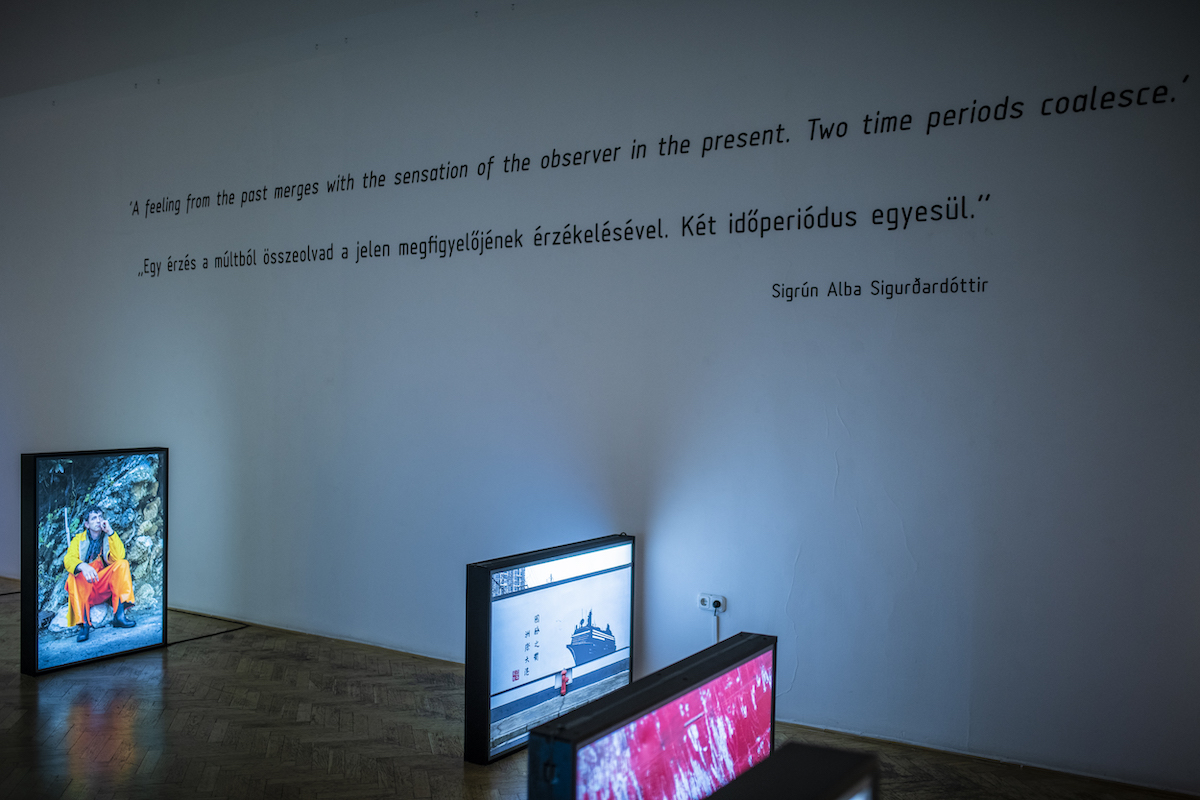

The photographer walks slowly around, alone outside in the daytime darkness, documenting the environment before him, adding a deeper meaning to it. The soccer goal by the shore, standing lonesome at 11 in the morning, when the first sunbeams of the day casts it’s light on the sea and glitters on the snow, which at that moment seems both wet and chilling, waiting for the children to be off from school and come back to play. Looking at this photograph, I sense again lost moments from my childhood. In that sense it’s like time stands still in Szalontai’s photographs, that the past and the present melts together, as they simultaneously depict the reality of the people living in Iceland in the 21st Century. A feeling from the past merges with the sensation of the observer in the present. Two time periods coalesce.

One can state, that a good artist does not only see what he expects to see but is willing to enter a dialogue with reality itself. It is like he is opening up for a resonance with reality or what the German sociologist Hartmut Rosa has descried as being open to the world, wanting to be affected and wanting to respond or answer.2 When in resonance with the world, one experiences “this other” which transforms her or him.3 According to Rosa: “Art should insist on the transformative element of resonance.” He explains: “[...] art is one sphere where we can explore different ways of being in the world and of relation to the world and I think really this is what art is about.”4 A photograph as a medium of art makes a space for the artist to meet the reality in both a realistic and dreamlike way, to affect and to be affected, to transform and be transformed, or to be in active conversation and at some moments also in resonance with the world. “Resonance is tied to an openness, of wanting to be affected and answering,“5 as Rosa explains it, and adds that even though resonance is always emotional and embodied it is not dissolved from the cognitive element, which I would like to add is also necessary for us to dwell creatively in the world.6

The artificial light that makes everything seem clearer, but also harsher to deal with Szalontai’s photograph of the quietness that can be found in the coldness of the night. As the soft light of the morning sun glittering on the corrugated iron of a renovated house in a remote fjord, as well as his photograph of the three sisters by a window in the January dimness, looking with some significance towards the photographer, combine an interesting story, inviting the observer to engage with and creating a poetic narration in resonance with reality about life in the past, the present and the future.

1 A quote from the story „House no. 451“ by the Icelandic author Gyrðir Elíasson. The quote is from Elíason‘s acclaimed short-story collection Between the Trees. Unpublished translation by Mark Ioli. See Gyrðir Elíasson, Milli trjánna. Smásögur, Akranes: Uppheimar, 2009.

2 Hartmut Rosa, Resonance. A Sociology of Our Relataionship to the World, transl. James C. Wagner. Cambridge UK: Polity Press, 2019 and Thijs Lijster og Robin Celikates, “Beyond the Echo-chamber: An interview with Hartmut Rosa on Resonance and Alienation.” Krisis: Journal for Contemporary Philosophy, 2019: Issue I, p. 72.

3 Thijs Lijster og Robin Celikates: “Beyond the Echo-chamber: An interview with Hartmut Rosa on Resonanace and Alienation,” p. 74.

4 Ibid, p. 68.

5 Ibid, p. 72.

6 Ibid, p. 76.

Bio

Ábel Szalontai, Balogh Rudolf Award-winner photographer, was born in Budapest in 1972. He completed his Visual Communication studies at the Hungarian University of Arts and Design in 1998. Following the university years and 5 years of working as a freelancer, he became studio head at the Photography Department of the university in 2003, design instructor in 2004, Head of Photography at the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design in 2006, and Head of the Media Institute in 2014. He received his doctorate in 2013, obtained habilitation in 2019, and presently he works as Associate Professor.

He was member of the Studio of Young Photographers, the Studio of Young Applied Artists, and the Association of Hungarian Photographers. His work has been supported and awarded via numerous fellowships, including the József Pécsi Photography Grant (1997, 1998), the Andre Malraux Fellowship, the Nancy Grant (2004), and he also received the Balogh Rudolf Award in 2015. He participates in and organizes numerous international symposiums, workshops and exhibitions. His works have been regularly showcased at solo and group exhibitions since 1998. In his work as an artist and teacher, he is mostly interested in exploring various phenomena through vision, and he researches the visual and narrative interrelations of the freedom of thought based on cooperation.

Thanks

Thanks to all those who collaborated on this exhibit: Sigrún Alba Sigurðardóttir, Gábor Arion Kudász, Virág Csejdy, Simone de Greef, Stuart Richardson, David Barreiro, Györgyi Falvai, Gabriella Nagy, Attila Pálfalusi, Gergő Gosztom